01

The rockrose and the lynx

The Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) is one of the four lynx species worldwide, found in southern and central Spain as well as Portugal. Meanwhile, the Cartagena rockrose (Cistus heterophyllus carthaginensis)—a shrub that can grow up to one meter tall and boasts striking pink flowers—thrives only in select spots along Spain’s eastern coast: the Sierra Minera of Cartagena near the Mar Menor (Murcia), parts of Valencia, and the La Cabrera archipelago in the Balearic Islands.

The Sierra Minera of Cartagena near the Mar Menor (Murcia), parts of Valencia, and the La Cabrera archipelago in the Balearic Islands. In the early 2000s, both endemic species, two of the most endangered of the Iberian fauna and flora, numbered less than 100 specimens, but thanks to ex situ breeding programmes (outside their natural habitat) based on genetic selection, they are successfully recovering: they have already been reintroduced into their respective habitats and have become international conservation references.

Ineco, through its work, such as the environmental processing of railway and road projects (such as the permeability and protection measures in lynx territory on the future Seville-Huelva high-speed railway line) and its participation in other environmental projects (such as the oversight of environmental restoration works in the Sierra Minera, one of the key initiatives aimed at recovering the Mar Menor), collaborates with the public administration in the conservation of these and other threatened or endangered animal and plant species by collaborating in other environmental projects.

To this end, it has more than 100 professional experts from multiple disciplines (biology, chemistry, geology, environmental sciences, industrial engineering, civil engineering, forestry, etc.) who contribute all their knowledge, including the use and development of the most advanced technological tools, in a wide variety of engineering and consultancy activities.

Consulting and engineering at the service of biodiversity

Placement of photo-trapping cameras during the field work for the study for the Burgos-Vitoria high-speed railway line. Photo: Ineco

Among the most recent projects, it is worth mentioning the environmental studies of linear transport infrastructure, such as those for the Seville-Huelva, Burgos-Vitoria and Nogales de Pisuerga-Reinosa high-speed railway sections, or the connection between Ávila and the A-6 highway. For these projects alone, almost 800 animal and plant species have been censused, a quarter of which are protected.

Other activities of the company are related to the management and protection of habitats in transport infrastructures, such as support to Aena and Adif in wildlife control services at airports and vegetation on the railway network. In the latter area, a web viewer has also been developed to facilitate this task.

Ineco is also carrying out biodiversity conservation work not directly linked to transport for the Ministry of Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge (MITECO), such as the environmental restoration of the Sierra Minera in Cartagena, and technical assistance in the construction of two aquatic species conservation and recovery centres (Margaritifera auricularia, in El Bocal, Navarre, and for the conservation of marine species, in Águilas, Murcia).

In the field of strategic consultancy, Ineco provides services to the Administration in the development of actions and transformations linked to major state plans such as the National Strategic Plan for Natural Heritage and Biodiversity by 2030.

Outside Spain, Ineco also oversees biodiversity protection efforts; for example, in Costa Rica, where since 2016 it has acted as the 'executing unit' for the Ministry of Public Works and Transport in national port and road plans, or in the Northern Latvia section of the Rail Baltica project, a major high-speed line of over 870 km that will cross the three Baltic republics.

02

Biodiversity: every species matters

A specimen of griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus) located during the environmental study of the Burgos-Vitoria high-speed railway line. Photo: Ineco

The concept of "environmental sustainability" spread worldwide following two events: the publication in 1987 of the so-called "Brundtland report" by the United Nations, which analysed the impact of human activity on the environment; and the holding of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in 1992, also known as the Rio de Janeiro Conference or the Earth Summit. This year also saw the creation of the European Union's Natura 2000 network, which covers habitats of interest and special protection areas for birds.

At the same time, the eminent American biologist Edward Wilson popularised in his works the concept of "biodiversity", which the United Nations had defined in Rio de Janeiro. which the United Nations had defined in Rio as "the diversity among all living organisms (...) in terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems", stressing that it "consists not only of variety among species, but also of genetic diversity within species and among communities of species, habitats and ecosystems". The UN Declaration also highlighted "the economic, social and cultural impacts and costs" and "the profound ecological, ethical and aesthetic implications" of biodiversity loss.

"Biodiversity is the key to maintaining the world as we know it.... Remove one species, and another rises to take its place. The loss of multiple species leads to the degradation of the local ecosystem”. Edward Osborne Wilson, biologist

Along with the concepts of biodiversity and environmental sustainability, the importance of conservation is also being disseminated. The basic principle is "every species matters", as demonstrated by numerous scientific studies that highlight the complex interrelationships between the elements that make up ecosystems. Thus, the growing environmental awareness of society and public administrations is reflected and integrated in legislation.

In Spain, mandatory environmental procedures for certain projects were introduced into legislation in 1986, following the country's entry into the European Economic Community In 2006 it was also extended to plans and programmes. In 2013 both procedures were legislatively unified, with subsequent modifications and updates, the latest in 2023.

In 1989, the first law on the conservation of natural areas and wild flora and fauna in Spain was passed, replaced in 2007 by the Law on Natural Heritage and Biodiversity, which created the list of species under special protection and the national catalogues of endangered species and invasive species.

In this way, the regulations become a tool at the service of nature conservation, when applied in studies such as those carried out by Ineco in the framework of the environmental processing of infrastructures.

The natural treasures of Spain

One of Spain’s most striking butterflies is the Spanish flag butterfly (Anthocharis euphenoides) one of the more than 5,400 species of Lepidoptera that can be found in Spain. Photo: Wikipedia

The Spanish territory is characterised by its extension and uniqueness, ranging from mountainous areas to islands, with more than 10,000 km of coastline, and a great variety of climates and landscapes. This exceptional ecosystem has given rise to the greatest biodiversity in Europe, with more than 50% of the animal species and 80% of the plant species of the entire European Union. Spain is also the country with the largest area protected by the Natura 2000 Network, accounting for 20% of the total.

Red-knobbed coot. Photo: Wikipedia

According to MITECO data, Spain has some 84,000 terrestrial and marine species, more than half of which are endemic. In total, more than 900 are threatened to varying degrees, including the Cantabrian brown bear, the Iberian lynx and wolf, the imperial eagle, the bearded vulture or the Cantabrian capercaillie, or unique trees such as the Canary Island dragon tree.

The European mink (Mustela lutreola) survives in only 3% of its former territories, in small areas of Romania, Russia and northern Spain. Photo: Life Lutreola Spain Project

Currently, nine species are listed as 'critically endangered'; seven of them have received this status since 2018. These include three birds — the lesser grey shrike, the marbled teal, and the Cantabrian capercaillie; two giant mollusks — one freshwater, the spengler’s freshwater mussel, and one marine, the mediterranean fan mussel; one mammal — the european mink; and one plant — the Cartagena rockrose. In 2025, the coot, a wetland bird of which fewer than 90 pairs are estimated to remain, and the Iberian desman, a small semi-aquatic mole with a long trunk considered a living fossil due to its rarity, were added to the list.

03

The silence of the bats

Riverside habitat in the study area of the Burgos-Vitoria high-speed railway, with alders, a key species for stabilising banks and purifying water. Photo: Ineco

Ineco has been carrying out environmental assessments of all types of transport infrastructures for more than 20 years. This is a complex and meticulous task that requires exhaustive work both in the field - including the in-situ evaluation of very different conditioning factors, for example, fauna, which usually requires visits that cover a complete annual cycle - as well as documentation and analysis in the office.

Some of the most recent environmental impact assessments have been carried out for high-speed rail sections such as the 95.5 km Sevilla–Huelva line, which received a favourable Environmental Impact Statement in 2024; the 90.7 km Burgos–Vitoria line, approved in 2021 (with construction of the first section, Pancorbo–Ameyugo, 8.4 km, awarded in 2025); and the 44 km Nogales de Pisuerga–Reinosa line, which received its Environmental Impact Statement in 2022 and is currently in the project drafting phase.

The analysis of specific environmental constraints related to fauna, flora, and other natural elements begins with the collection of information from various bibliographic and cartographic sources — including national and regional lists of protected species, habitats of community interest, and the Natura 2000 network. This process aims to produce an initial inventory of wildlife and vegetation, their estimated locations, protection categories, and associated biotopes. Subsequently, vegetation studies involve field surveys to inventory the various habitats — wetlands, marshes, grasslands, steppes, riparian forests, other native woodlands, meadows, reforested areas, and more — and to identify which of them are considered 'Habitats of Community Interest' (HCI). This information is then used to produce detailed maps of the environmental constraints in the area.

"The consultant will carry out an in-depth study of the different habitats and species of fauna present in each affected area, with the aim of establishing measures to contribute to guaranteeing biodiversity and the conservation of natural habitats and fauna, in accordance with current legislation, and in coordination with the competent administrations". Adif's specifications for the drafting of fauna and flora studies for the Nogales-Reinosa HSL.

Where field work is carried out after the initial desk-based work, to confirm the presence and actual distribution of species in the area. Observation points and sampling methods are established, depending on the characteristics of the project and the habitats of the groups to be observed - diurnal or nocturnal, resident or migratory, aquatic, flying or terrestrial species, etc.

At this stage of the study, consultants team collects data during field visits through direct observations—either on foot or in slow-moving vehicles along predefined sampling points—or through sightings and indirect methods such as camera traps, tracks (footprints, droppings, shells like those of Margaritifera auricularia found in the Ebro River during the Burgos–Vitoria high-speed rail study), or other even more specific techniques.

Specimens of protected species found during fieldwork: false cress (Anthionema thomasianum), and San Antonio frog (Hyla molleri) from the study of the Nogales-Reinosa HSL. Fox footprint (Burgos-Vitoria HSL study) and hairy clover (Marsilea strigosa) (Seville-Huelva HSL study). Photos: Ineco

This is the case of ultrasound recordings to identify different species of bats (very sensitive to the loss of refuges and the alteration of their ecological corridors), as in the Nogales-Reinosa study. The ultrasounds they emit are not perceptible to the human ear, so the only way to process them, once recorded with a special detector, is by visualising and comparing their graphic representation or sonogram using specific software (in this case, Kaleidoscope Analysis). In other words, the consultants record the "silence" of the bats in order to identify them.

Once the types of habitats, ecological corridors and animal and plant species present in the study area have been identified, in addition to other environmental conditions, the types of impacts for each of the layout alternatives are estimated, distinguishing between temporary ones (during the construction phase) and permanent ones (exploitation phase) such as the barrier effect, the definitive loss of vegetation, mortality due to collisions and electrocution of flying fauna (birds and bats), or due to being run over (mammals, amphibians and microfauna), among others.

Young male Iberian lynx (Photo: CENEAM photo archive, MITECO), a species for which numerous protection measures focusing on permeability have been implemented in the faunal study of the Seville-Huelva high speed railway, and the red-breasted axonbird or "vineyard bird", (Photo: Quique Marcelo-SEO Birdlife), in danger of extinction, for which temporary restrictions have been established during the works phase to avoid noise.

It is also analysed whether the presence of other nearby infrastructures (for example, a highway close to a new high-speed line, as in the study of the Seville-Huelva high-speed railway) could cause synergistic effects on the impacts already detected.

Based on all these criteria, the different alternatives are ranked and compared. One of the selection criteria in the study of alternatives is environmental.

Subsequently, preventive, mitigating or compensatory measures are proposed for each alternative. For example, in the case of definitive loss of vegetation, plantations or reforestation of the same or a larger area in another location can be proposed.

04

Connecting to protect

At the design stage, during the conception of the infrastructure, consideration is given to layouts and structural solutions that have the least possible impact on fauna and flora. The most commonly used solutions are to bury or raise the route with tunnels and viaducts (Seville-Huelva, Nogales-Reinosa, Burgos-Vitoria), which can also be applied to associated installations such as power lines (as in the Seville-Huelva high-speed railway, where it is proposed to bury 6,500 metres of power line).

During construction, the most common measures include temporary restrictions (biological stoppages) during breeding and nesting seasons of the most sensitive species, minimizing land occupation, and limiting the movement of machinery and workers to clearly marked and fenced work areas. There is also a requirement to restore all access roads, avoid altering watercourses or aquifers, reuse local soil whenever possible, prevent spills, and instruct workers on the species to be protected, etc.

Cantabrian brown bear and bear corridor (Nogales-Reinosa high speed line) Photos: Cabárceno Park/ Ineco

For the exploitation phase, the main objective is to guarantee faunal permeability, that is, to allow fauna to move along their usual corridors (which will have been previously located) and thus avoid the fragmentation of habitats, one of the greatest threats to the conservation of biodiversity. To preserve ecological connectivity, environmental studies (aligned with current regulations) primarily recommend the installation of wildlife crossings. These structures are carefully designed and strategically located based on the species expected to use them, including large vertebrates, medium-sized mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. For instance, in the environmental assessment of the high-speed rail line between Seville and Huelva, the proposal includes one wildlife crossing every three kilometers for large vertebrates, and one per kilometer for smaller species. In key strategic areas, this density increases to one and two crossings per kilometer, respectively.

To guarantee the effectiveness of the wildlife crossings, they must be arranged in such a way as to encourage their use by the species present in the direct surroundings of the linear infrastructure, by means of vegetation or other elements.

“Ecological connectivity is of great importance in the conservation of biodiversity, given that species of wild fauna and flora must be able to make dispersive movements with which to maintain certain levels of genetic exchange between populations and with which to eventually occupy suitable habitats in which to settle. Strategy for the defragmentation of habitats affected by linear transport infrastructure”. Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, 2024

Transversal drains can also be adapted as wildlife crossings, adding side banks or "dry banks" for terrestrial fauna, and, if there are watercourses, design the bottoms avoiding excessive slopes to facilitate the passage of fish and other aquatic fauna.

Perimeter fencing, while enhancing road safety, also plays a crucial role in wildlife protection. It helps prevent animal-vehicle collisions and restricts access to prey species that could attract predators. For example, wild rabbits (key prey for the Iberian lynx and numerous birds of prey) are managed along infrastructure such as the Seville-Huelva high-speed rail line and the Ávila highway. Excessive rabbit populations can also compromise the stability of embankments and cuttings, making fencing a dual-purpose measure for both ecological and structural integrity.

Various types of wildlife crossings and fencing systems installed along Spain’s high-speed rail lines. Photos: Ineco Archive

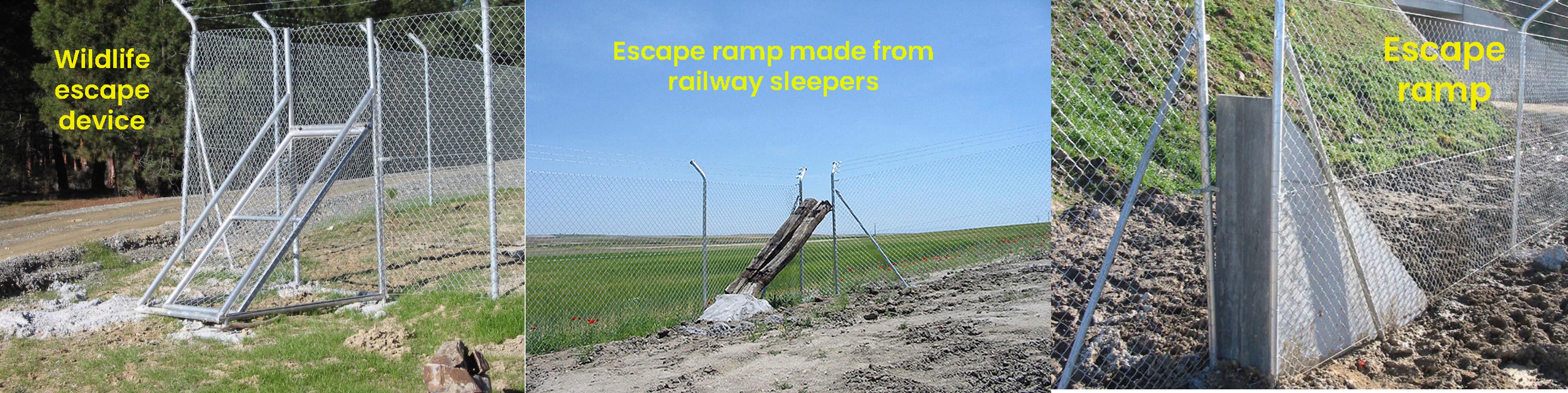

Fences must have the resistance, height and design specific to the type of fauna in the area: for large and medium-sized animals, such as ungulates, bears, wild boars or lynxes (that can jump more than two metres), without forgetting smaller animals that can climb (amphibians, reptiles) or burrow (rabbits and hares, genets, foxes, etc.). For this purpose, the lower part of the fence is reinforced and buried in the ground. In addition, they must be equipped with suitable escape devices, such as gates for large animals, or ramps in chambers or gutters to allow small animals that may be trapped to escape.

Fences with escape devices installed on high-speed lines. Photos: Ineco Archive

For instance, in the environmental assessments of the Nogales–Reinosa and Seville–Huelva high-speed rail lines, fencing has been specifically designed to deter bears and Iberian lynxes. These barriers reach up to 2.5 meters in height and feature triple-twist mesh, a 50-centimeter overhang angled at 45 degrees at the top, and a lower section with fine mesh buried at least 30 centimeters into the ground to prevent digging.

With regard to birdlife, one of the main protection measures is to avoid collisions both with the infrastructure itself or vehicles and with associated installations, such as power lines (catenary). Thus, for example, viaducts and raised sections of the route are equipped with anti-collision screens for birds.

These screens consist of pointed posts—designed to prevent birds from perching—standing at least five meters tall and painted in colours that contrast with the surrounding landscape. In some cases, earthen embankments or even trees are used, particularly for bats, as seen along the Ávila highway. Additional measures include reducing light intensity in urban areas and eliminating insect-rich ponds that could attract these species.

With regard to the prevention of bird electrocution on high-voltage power lines, it is estimated that between 11,000 and 30,000 birds die each year as a result. Ineco has been working in this specific area at a national level since 2004. To this end, it has a team of specialists who draw up projects and monitor the execution of these measures, which mainly consist of installing insulating and signalling elements. These types of measures are also included in environmental studies such as the Nogales-Reinosa high-speed railway.

As far as vegetation is concerned, the main measures in the event of the presence of protected species may be the collection of germplasm (seeds, bulbs, cuttings, pollen, etc.), translocation of specimens or, where appropriate, compensatory measures such as revegetation with native species and improvement of equivalent areas, i.e. with similar characteristics to those affected, but in a different location. An example is the reforestation of holm oak and riparian forests planned in the study of the Burgos-Vitoria high-speed railway.

All the measures proposed (preventive, corrective or compensatory) are subject to monitoring to assess their effectiveness and correct deficiencies, by means of environmental monitoring programmes before, during and after the works, for periods which may vary, depending on the type of measure, from several years to the entire useful life of the infrastructure, as in the case of the obligation to maintain fencing and wildlife crossings on the Seville-Huelva high-speed railway.

Mangroves and moose

Beyond Spain, Ineco is also involved in transport infrastructure projects around the world that incorporate biodiversity protection measures.

Northern tamandua in Costa Rica. Photo: Archive

Thus, in Costa Rica, the company has been responsible since 2016 for the technical, legal and environmental management of the road and port development programmes (PIT and PIAVVV, both financed by the Inter-American Development Bank). Acting as the “executing unit” for the Ministry of Public Works and Transport, Ineco has overseen the construction and improvement of roads across Costa Rica—including sections such as Playa–Naranjo–Paquera, Barranca–Cañas, Barranca–Limonal, and Limonal–Cañas—where a total of 140 wildlife crossings (78 underpasses and 62 overpasses) and 52 warning signs have been installed. These measures aim to protect some of Costa Rica’s most threatened species affected by roadkill, such as the northern tamandua—a type of anteater—felines like the ocelot, medium-sized mammals including coatis, raccoons, badgers, and grey foxes, as well as reptiles like the green iguana and birds such as the common black vulture.

The company has also supervised compensatory actions related to vegetation, in projects such as the improvement of Route 17- La Angostura, and the Puerto Paquera ferry terminal, such as the planting of a total of more than 3,700 trees or the rehabilitation of 50 hectares of mangrove in the Gulf of Nicoya. In addition, and also as a compensatory action, roads, accesses and signposting have been rehabilitated and improved in the Cabo Blanco nature reserve.

In Europe, Ineco has also supervised the fauna and flora study of the Latvia North section (from the border between Estonia and Latvia to the city of Vangaži, 94 km long) of the Rail Baltica project, a high-speed line that began construction in 2024 and will connect the three Baltic republics with the rest of Europe over more than 870 km.

The studies, carried out between 2020 and 2022, catalogued a wide variety of species such as elk, wild boar, deer, bear, fox, wolf, raccoon and lynx, as well as small mammals such as squirrels, hares, martens and otters, present in all water bodies along the Northern Latvian section. As a result, the construction of six ecoducts and one underpass was planned to facilitate the migration of large and medium-sized mammals.

In total, more than 40 large wildlife crossings, both overhead and underpasses, will be constructed along the entire line.

As for the flora, possible effects on protected trees of species such as silver birch, oak, aspen and pine were studied and ruled out..

05

Conservation, at the centre

Specimen of Margaritifera auricularia next to its host fish, the river blenny. Photo: Breeding centre of La Alfranca, Zaragoza

This is a large river mollusc, measuring 17–20 cm—the largest freshwater mollusc species—which can live up to a hundred years… if its extinction can be prevented. The causes of its decline are the alteration of riverbeds, industrial, urban and agricultural pollution, competition from invasive species such as the zebra mussel or the Asian clam, and its extraction for its nacre. Its presence is considered a bioindicator of high river water quality, and outside Spain there are only references to small populations in some French rivers, such as the Loire.

Known as the "margaritona", its population, concentrated in Aragon and Navarre, once numbered up to 6,000 specimens, but it has declined so much in the last 20 years that it has been declared "critically endangered" in Spain, a consideration that implies, by law, the development of a conservation plan and the "urgent" processing of actions.

For this reason, in 2005 the governments of Aragon and Navarre, together with the central administration, started a conservation and captive breeding programme, with a centre in La Alfranca, Zaragoza, which has recently been joined by a second one located in El Bocal, Navarra (Canal Imperial de Aragón), designed by Ineco and the result of an agreement between administrations signed in 2021.

The first results of the breeding programme are promising. And it is not an easy process: although these mollusks are hermaphrodites, they require the collaboration of a host fish, a kind of nanny that temporarily houses the larvae or glochidia in its gills (without causing damage), which are later released to continue their development. Breeding in controlled conditions, and subsequent release, seem to be confirmed as the only options for the survival of the species which, in the most optimistic scenario, could become the Iberian lynx of molluscs.

A fate that could be shared by the noble pen shell (Pinna nobilis) endemic to the Mediterranean, another large bivalve (up to 120 cm) that is also on the list of "critically endangered" species.

Project for the future State Centre for the Conservation and Pre-production of marine species, in Águilas, Murcia. Image: MITECO

Ineco is in charge of the project management of another centre that could help save them from extinction: the State Centre for the Conservation and Pre-production of marine species of the Mediterranean and the Mar Menor, located in Águilas (Murcia). The works, which began in February 2025, are scheduled to last 18 months. Covering 6,750 m², the facility will be divided into three areas: a scientific zone for research, a lagoon area for breeding marine species—including Posidonia oceanica, the natural habitat of the noble pen shell —and a visitor area dedicated to public outreach.

View of the Mar Menor from the Sierra Minera. Photo: Ineco

The Águilas Centre is part of the planned actions under the environmental recovery program for the Mar Menor, Europe’s largest saltwater lagoon. Despite its rich natural value, the area has been severely degraded by human activity, which has disrupted the entire surrounding ecosystem, including its drainage basin. Since 2019, the entire area has been the subject of one of the most complex and ambitious comprehensive environmental restoration programmes in Europe, recognised by the United Nations as the "flagship initiative for ecosystem restoration".

The programme consists of 10 major lines of action, which include projects such as the environmental restoration of the Sierra Minera de Cartagena, which aims to prevent sediment from reaching the lagoon through runoff. Since 2022, Ineco has been providing management and technical control services for the works, health and safety coordination, environmental monitoring and dissemination tasks for the Directorate General for Water of the Ministry for Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge, (MITECO, in Spanish). The project is currently in its second phase, after the execution in 2023 of the main actions, consisting of the construction of 60 dykes and two large areas of bank protection with riprap in the wadis, as well as measures to improve biodiversity, such as planting of vegetation and installation of shelters and nests for birds, bats and insects.

06

The hawk and the grass

During the operation phase of transport infrastructures, there are also other specific aspects that have implications for wildlife conservation.

The growth of vegetation on the margins and platforms of roads and railways poses a risk of fire, can hide signposting and damage the road surface or ballast, altering its cushioning and drainage capacity, as well as acting as a focus for attracting wildlife, thus increasing the probability of being run over.

For this reason, Adif, the state railway infrastructure administrator, periodically contracts a vegetation control service, to which Ineco provides technical assistance services for evaluation and supervision.

In order to keep the tracks and their surroundings free of vegetation, work such as clearing, felling and pruning is carried out continuously, which increases railway safety by minimising the risk of fires and preventing incidents such as trees falling on the tracks, as well as controlling the proliferation of invasive species.

These mechanical works are complemented with two annual treatment campaigns throughout the network, with specifically authorised phytosanitary products, which are applied by means of an herbicide train or by operators with autonomous equipment.

To avoid damage to the environment, preventive measures are established such as safety bands to avoid damage to crops (five metres) or bodies of water (20 metres), or to avoid application on rainy days or in strong winds.

Between 2018 and 2025, within the framework of technical assistance, Ineco is developing an application specially designed to facilitate the control and supervision of these works, a web viewer based on geographic information systems, in which the information of the inspected actions is dumped, registering all the activity. This centralises the information and makes it accessible to all operational deputy directorates. The viewer provides support in the control of certification, detects problem areas, selects the appropriate treatments, avoids duplication, prioritises actions, etc. Moreover, it can be extended to other types of activities and infrastructures.

The viewer developed by Ineco makes it possible to visualise and supervise all vegetation control activities, as well as to record incidents. Images: Ineco

It is an example of how a technological tool can contribute to the preservation of biodiversity, since by increasing the control and precision of actions, it avoids affecting protected species, optimises treatments (not felling or pruning specimens that do not correspond) and treats invasive species in an appropriate and proportional manner.

In 2014, the company began supporting the Spanish Aviation Safety and Security Agency (AESA) in wildlife control at airports and in assessing bird strike risks, one of the most significant threats to air operations. Since 2017, it has been providing consultancy and technical assistance services in this field to Aena. One of the most effective prevention methods is the use of specially trained birds of prey, a service created by Spanish naturalist Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente in 1968, initially at the Torrejón de Ardoz air base under the name 'Operación Baharí' (Baharí Operation - falcon, in Arabic), and two years later at Madrid-Barajas airport. Other scaring methods are also used, such as alarm sounds, lights and pyrotechnics, raids or capture of individuals and removal of nests in conflict areas.

"The repercussions of impacts with fauna on operational safety, as well as the consequences from an economic point of view, are appreciable and require a preventive approach and an integrated application of different measures and actions to reduce this risk, both in the vicinity of the airport and in the rest of the national territory." State Aviation Safety Agency, 2019

It is also necessary to control the incursions of terrestrial wildlife, both wild and feral (which includes all types of animals, such as deer, wild boar, foxes, etc.) and prevent them from accessing the runways or other areas.

The aim is to avoid sources of attraction, such as grassy or fruit-bearing vegetation, or the presence of prey species such as lagomorphs (rabbits and hares) and other small mammals. To this end, captures are carried out for their subsequent removal or, where appropriate, hunting control. In addition, the management of habitats around the airport that may attract fauna (dunghills, rubbish dumps, wetlands, golf courses, etc.) is coordinated with third parties.

Since 2024, Ineco has been supporting Aena’s Central Operational Safety Office with key activities such as on-site technical supervision, assistance in drafting tender documents for wildlife control studies and services, proposing actions, developing monitoring methodologies, responding to airport inquiries, and validating wildlife collision risk assessments.

25 years watching over nature's work

Ineco has been involved in the development of high-speed rail in Spain since its beginnings, from the first study carried out for Renfe in 1972 (Madrid-Barcelona-Port Bou) to the present day and has also been a pioneer in the environmental management of works. This role was introduced into legislation in the mid-1990s as a means of supporting and ensuring the implementation of preventive, mitigating, and corrective measures arising from environmental impact studies and declarations (EIDs) and materialized through environmental monitoring programs.

Since 1999, when the GIF (predecessor of the current Adif) entrusted Ineco with these tasks for the first time, on the Madrid-Zaragoza-Barcelona high-speed line on the French border, more than 25 years have passed in which the company has participated in all the lines of a network that now totals 3,700 km, the second longest in the world. Thus, once the execution phase has begun, the environmental management of the work also becomes a tool to contribute to the protection of nature.

This extensive field experience is very valuable for assessing the effectiveness of measures such as wildlife crossings. A recent example is the pilot experience of of real-time monitoring by video surveillance carried out from 2022 to the present day in the Otero de Bodas (Zamora) ecoduct, on the Madrid-Galicia high-speed railway, Olmedo-Ourense section.

Fauna captured with video surveillance cameras in the Otero de Bodas ecoduct deer, roe deer, wild boar, foxes and wolves. Images: Ineco

Other examples of singular biodiversity protection actions carried out within the framework of Ineco's environmental directions over the last 25 years are:

2022: Road on viaduct (Badajoz), Madrid-Extremadura high speed railway, Cuarto de la Jara-Arroyo de la Albuera section. Instead of replacing on the surface the EX 209 road, located in an area of high environmental sensitivity, Adif AV built a 352 m long viaduct bypass, which has led to a defragmentation of the Río Aljucía SAC.This has led to the defragmentation of the ZEC Río Aljucén Bajo and the ZEPA Embalse de Montijo, notably improving the permeability of the fauna by avoiding the barrier effect of the old road in addition to the new high speed line.

Captured specimen of desman. Photo: Adif

2012-2019 Protection of the Pyrenean desman (Zamora), Madrid-Galicia high speed railway, Zamora-Pedralba de la Pradería section. One of the last remaining populations of the Pyrenean desman, a small mammal endemic to the Iberian Peninsula, is preserved in the watercourses around Sanabria. Highly endangered, it lives in mountain streams with a permanent flow, with clean, oxygenated water.

For the protection of this species, the environmental management of the works ensured the implementation of mitigating measures such as exhaustive control of effects on watercourses, water quality, flow maintenance and environmental restoration. In addition, operations to capture and translocate specimens were supervised in the Special Conservation Area (ZEC, in Spanish) of the river Tera and its tributaries, in the vicinity of the Los Pedregales viaduct. More than twenty individuals were captured and implanted with a small transmitter to study unknown aspects of their biology, such as their vital domains and core areas, as well as their movements.

2010-2012: Sorbas tunnel (Almeria), Madrid-Murcia-Almeria high speed railway. Site management of a 7.5 km twin-tube tunnel, the longest in Andalusia, to minimise the impact on the environment, a semi-desert ecosystem (Site of Community Interest, SCI Sierra de Cabrera-Bédar) with species such as the endangered Moroccan tortoise.

Sorbas Tunnel under construction and a specimen of the Moroccan tortoise ( Testudo graeca) Photos: Ineco/Fundación Biodiversidad

Viaduct of the Ulla. Photo: Ineco

2008-2011: Viaduct over the river Ulla, (A Coruña) on the Ourense-Santiago axis, Madrid-Galicia high speed railway, subsection Silleda (Dornelas)-Vedra-Boqueixón. Environmental management of the construction of a large viaduct 630 m long, 117 m high and 168 m span, designed to protect the Site of Community Interest (SCI) "Ulla-Deza river system", with protected species of riverbank vegetation such as alders, willows, river ash trees, and aquatic fauna: Atlantic salmon, sea lamprey and trout. The project received the Aqueduct of Segovia award for, among other achievements, the degree of environmental protection achieved during its construction.

Fish ladder at the weir (irrigation dam) of Molins del Rei. Photo: Ineco

2003-2010: Ecological integration in the Llobregat river, Madrid-Barcelona-French border high-speed railway: naturalisation and revegetation of riverbanks, restoration of riverbed, enlargement of wetlands in Molins de Rei (Aiguamolls) and construction of fish ladders. Other actions: construction of burrows for otters, installation of nesting boxes for birds, monitoring of the colony of bats in the Puig d'en Marc cave, monitoring of the reproductive cycles of rupicolous birds of prey, mainly Bonelli's eagles.

Tree transplants on the Madrid-Valladolid high-speed railway. Photo: Ineco

2003-2007 Tree transplants on the Madrid-Valladolid high-speed railway (Madrid): transplants of holm oaks, almond, pine, olive, strawberry and cork oak trees in the towns of Tres Cantos and Colmenar Viejo; creation of visual screens with pine and juniper trees on the service roads.